Field Snapshot: Cultivating the Memory of Soil

Doctoral candidate María Touceda-Suárez collaborates with a local living agricultural museum to better understand how land use impacts microbial communities.

Deciding where to sample soil in Mission Garden, a living agricultural museum located right by Sentinel Peak (A Mountain).

On a hot October afternoon, María Touceda-Suárez (link is external)meticulously scopes soil samples in Tucson’s Mission Garden(link is external), a nonprofit and volunteer-based organization working to preserve thousands of years of agriculture on the Santa Cruz river basin.

To gain field and outreach experience, doctoral candidate María Touceda-Suárez is working on a pilot project at Tucson's Mission Garden.

“I’m intrigued by how microorganisms impact us and how we impact them.” She explains moving between fruit orchards and vegetable gardens. “I’m especially curious about long-term--or legacy-- effects of agricultural activities on soil microbial communities.”

Normally as a data scientist and bioinformatician, Touceda-Suárez would receive this data at her computer. But she wants to gain practical field experience and become involved in outreach while pursuing her doctorate at the University of Arizona.

After her faculty advisor, assistant professor Albert Barberán(link is external), introduced her to the Mission Garden, Touceda-Suárez thought it would be perfect for a small pilot project that combines several of her interests: microbial ecology, soil science and sustainability.

Examining Legacy Effects of Agriculture

Millions of microbes live in a single gram of soil. These microscopic communities show a temporal picture of the innerworkings of soil biology, chemistry and physics. But the careful equilibrium of living and non-living features in soil is easily upset.

“Intensive agriculture can harm the soil and disrupt microbial communities for many years. This is a huge issue on a global level in terms of the sustainability of our environment.” says Touceda-Suárez.

Touceda-Suárez wants to study these legacy effects, or what she calls the ‘memory of soil.’ The complex nature of soil health can make these effects difficult to discern. But the unique nature of the Mission Garden provides the perfect scene for a pilot project.

Doctoral candidate María Touceda-Suárez and postdoctoral fellow Gabriele Schiro collect soil samples from various agricultural plots in Mission Garden.

Archeological work unearthed how this floodplain along the Santa Cruz River has a 4,100-year agricultural history, including S-cuk Son, the O’odham village from where the name Tucson originated.

Now, the Mission Garden works to interpret this history in various plots to in order to preserve, transmit and revive a rich agricultural heritage. In a small and pseudo-controlled space, Touceda-Suárez can analyze soil from various crops to better understand different agricultural traditions.

Personalizing Soil Health

For her project, she sampled soil from 12 plots and two control sites (where no crops had yet been planted), including Spanish colonial fields, orchards and vegetable gardens, desert natives, early agriculture, Hohokam, O’odham (pre- and post- contact), Mexican and Chinese.

With the soil, she will extract DNA for genomic and biogeochemistry analyses. With this information, she wants to help Mission Garden understand baseline similarities and differences in their soils.

“I want to get a picture of various microbial communities. In the future, we could use this data to personalize our soil systems like we personalize our medicine, depending on its composition.”

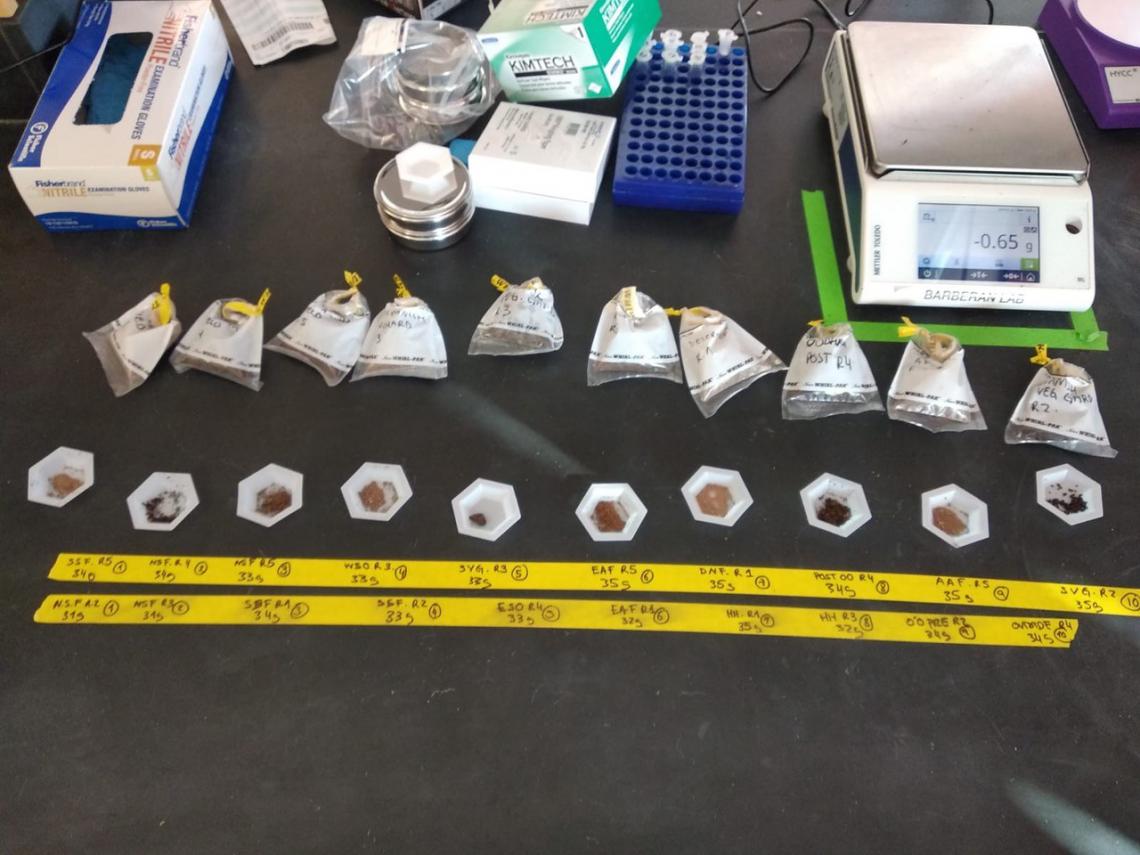

Soil samples from Mission Garden will be analyzed to examine microbial communities and biogeochemistry.

Touceda-Suárez hopes this pilot project is just the beginning of a closer collaboration with Mission Garden and local community.

As a volunteer at the garden, she looks forward to continuing to share her knowledge with the visitors of the garden with posters, presentations and demonstrations that connect people with the beautiful complexity of life in our soil.